ANDY GARCIA, who came from Cuba as a young boy in 1961, remembers his first homes in Miami clearly: one-bedroom efficiency apartments, in what was then down-at-the-heels Miami Beach. He also remembers the jobs his father, who had been a lawyer in Cuba, took: working for a catering company, delivering socks on consignment. During the socks era, their home was the warehouse. The living room was O.K., Mr. Garcia says, laughing, but when you walked into the hallway or the bedroom there were boxes of socks everywhere. Every night after dinner, Mr. Garcia and his family sat at the table and sorted them, putting in little plastic hangers. He was pretty good at it, he says. He developed a system. It is a story out of Horatio Alger, except for the Cuban music of the 50's: Andy Garcia, The Little Sock Boy. And without the music, which he has championed, you do not have Mr. Garcia.

Now, of course, Mr. Garcia, whose film about his native country, "The Lost City," opens this Friday, is a movie star. He has two homes, one in California, one here in Florida. This one, which Mr. Garcia and his wife built in 1999, was inspired by an old plantation house in Cuba. It has wraparound verandas, five bedrooms, a pool and a studio where Mr. Garcia, who plays conga and piano, can write and make music. Two fishing boats, one a 34-foot Venture, are kept in the backyard bay. Mr. Garcia stands on his pier, smoothly dressed in a cobalt blue linen shirt and off-white linen pants, wearing socks that pick up the colors of both.

Talking about the Cuban Revolution, he is a serious man, but walking about his home, his happiness is obvious. He talks about the porpoises in the bay, the manatees, the alligator they occasionally see.

He admires a neighbor's speedboat that goes racing down the bay. "See how beautiful that thing is!" He shouts across the water, "I want to go for a ride in that thing."

The view of his house from the pier is paradisiacal: a tiered wedding cake of white verandas, giving way to lawn and pool in the foreground, giving way to the dock at your feet.

The story goes that his family was so destitute when they arrived, his mother had to borrow a dime to call a relative to come get them. She must be very happy when she sees this house.

"She was very happy that she saw her children be very successful through the grace of God to enjoy the fruits of their labor," Mr. Garcia says, now very earnest again. "Nothing in life comes easy, you gotta work for it." There is a brisk segue to the subject that has brought the interloper to his home, Mr. Garcia's new movie. "It took me 16 years to try to find support for it," he says. "I never got support in Hollywood."

Written by the Cuban novelist Guillermo Cabrera Infante, "The Lost City" tells the story of a middle-class family torn apart by the Cuban Revolution. Mr. Garcia, who directed and wrote the score, stars as Fico Fellove, a nightclub owner who must choose between Castro's Cuba and freedom and who — and this is not unimportant to a fellow who says 'Casablanca' is one of his favorite movies — gets to wear those white dinner jackets. Dustin Hoffman has a cameo as the gangster Meyer Lansky —Mr. Garcia saw the elderly Lansky walking his little white dog on Collins Avenue when he was a boy, and he felt Mr. Hoffman would be perfect for the role. With a budget of $10 million, Mr. Garcia shot the film in the Dominican Republic in 33 days, fitting it in between stints of work on "Ocean's Twelve."

Mr. Garcia speaks often of his nostalgia for the Cuba his family left behind. But he was 5 years old when they left. Does he actually remember anything about Cuba?

"Are you kidding?" he says.

"The family's farm, the soil, how it felt, the coldness of the terrazzo floor. I remember when they were strafing Havana during the Bay of Pigs. Picking up the .22-caliber shells from the anti-aircraft missiles. Hiding under the bed. I remember my grandmother playing the piano."

He recalls leaving Cuba with his family and going into the glass-enclosed area that the exiles called la pecera — the fishbowl. His older sister was wearing bangle bracelets which the military police could not remove. When one returned with clippers, he thought they were going to cut her hand off.

He remembers the stories his parents and grandparents told.

"I have a lot of memories and I began to build on top of that, as a young boy who was enamored of the music of the 1950's. Then as I got older I started to read and research Cuban history and music. I transformed myself there since I couldn't be there. I was profoundly in love with that era of Cuba."

It sounds as if he was picking up something in the air about him, as he was growing up.

"Pain, deep pain," Mr. Garcia says. "It's the tragedy of exile, when you have to leave the thing that you most cherish." He speaks of the nightclub owner he plays in the film, who leaves Cuba carrying record albums. "In the movie, they say to him, 'You can't take Cuba with you.' He does. He builds Cuba in exile. That's what I did. I live with Cuba every day."

Mr. Garcia has been married for 24 years to Marivi Lorido, a Cuban American whose family story was much like his own. Their main home is in Los Angeles. But in the spring of 1991, when Mrs. Garcia was pregnant with the third of their four children, they bought a house in Key Biscayne to be near their families. Their children have 22 first cousins on Biscayne Bay.

They paid $1,250,000, and the next year Hurricane Andrew hit. A cypress fell across the house, the water came up to the doorknobs on the lowest floor, there was sand and fish in the washer. The Garcias knocked it down and, with the help of Deborah De Leon, an architect friend, built their current house. It began with a sketch that Mr. Garcia gave Ms. De Leon, which, like so much in his life, was based on research of a dream of Cuba.

The idea was to build a home that would look like it had been there since the 1920's or 30's. (He declined to say what the house cost, but a Miami-Dade tax assessment of 2005 listed the value of the building at $1,770,354 and the value of the land at $2,183,850.) The exposed ceiling beams are structural, made from Guyanese hardwood; the bathrooms have big, clawfoot tubs and reproduction period hardware. "There is a lot of cross ventilation," Mrs. Garcia says. "Where there is a door or a window, you'll see a door or a window opposite, which is I hear is not good for feng shui. You're not supposed to have the front door and back door aligned. That's why this house is a money pit. Money goes in, money goes out."

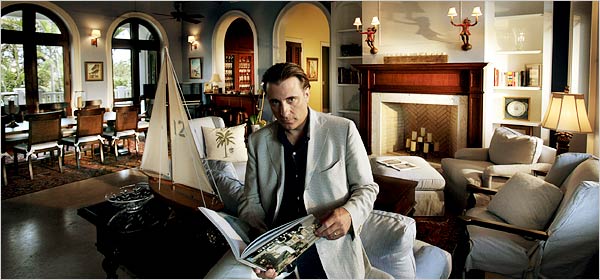

It is also a very welcoming house, where a love of music is evident. The table in the great room seats 12. Beside it are two 1950's Cuban conga drums which Mr. Garcia restored, along with his Steinway and a small bar. On the wall is a collage of Mr. Garcia, crazy with happiness, playing the congas with his boyhood idol, the mambo bassist Israel López, known as Cachao, on bass. Mr. Garcia produced and performed on Mr. López's Grammy award-winning CD, "Cachao — Master Sessions."

"This place is a very casual house for us," Mr. Garcia says. "We live mostly in L.A. and come here in summer and for vacations. It's a house that can receive a lot of people, where you can meet together, have some cocktails, jam together. That's the idea of a Caribbean great room, a central hall where everything would happen. My little boy rides his bike through here."

But what of the hurricanes, Mr. Garcia is asked. He has already lost one home in this spot. Mr. Garcia is not concerned. He and his wife have lived with hurricanes all their lives, he says. The first floor of the house is lifted now; the garage is at ground level, but they have sump pumps.

"You can't get insurance for the first floor," Mr. Garcia says, "But you say O.K., that's fine. This is the price you pay if you want to live in paradise."